Tag: Featured

-

Performance and Audience in Larp

“When we larp, some of the time we are in a performing role, and some of the time in an audience role. And that is ok! It’s the same in real life, after all. We shouldn’t see this as larp falling short of an aesthetic ideal in which such concepts don’t apply. Larp doesn’t have…

-

Emotionally Pacing for Larps – How To Get the Best Rollercoaster Ride

“Pace yourself and pace your design. Intense emotional experiences become more available to you and more sustainable if you have variety to the intensity of your play, both as a designer and as an individual player.”

-

Games Never Played: or Composting ‘The Antarcticans’

“If larp is a co-creative practice, one that cannot exist without its players, what do we call larps that were never played? And what do we do with them? Can we still give them a life outside of ourselves, and enjoy their unpredictability?”

-

Christianity is an Immersion Closet

“Never, before the recent re-run of the larp Snapphaneland, had I had religious play as deeply immersive and moving.”

-

River Rafting Design

in

River Rafting design can help create a more engaging and dynamic player experience from the very beginning of a larp, with a higher chance of many moments of emotional impact, instead of very few towards the end.

-

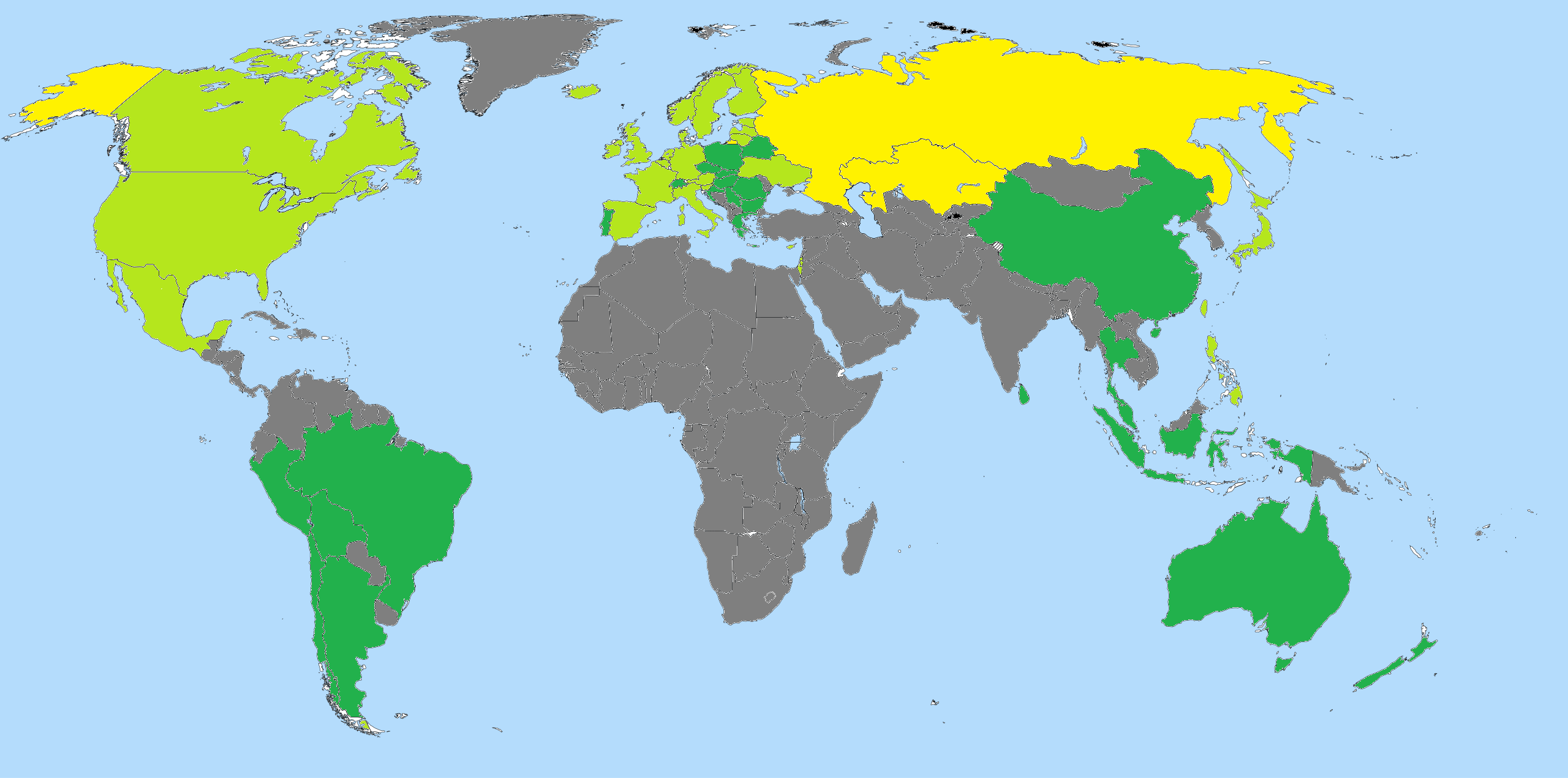

Larp in Greece, Romania, and Switzerland

A summary of the history of larping and the current larp scene in three European countries, as learned from local larpers, taken from the author’s collection of articles on larping around the world.

-

Experiencing Art from Within

In Kaisa Kangas’s larp Hyvät museovieraat (Eng. Dear Museum Visitors), in the Amos Rex museum, artworks came alive and possessed the bodies of the participants.

-

Playing First Contact in Eclipse, a Spectacular 3-day Sci-Fi Larp

The larp Eclipse “was like a simulated near-death experience, an attempt to convince players they were on the brink of unimaginable transformation,” reflects Adrian Hon, in this detailed and thoughtful article: spoiler warning!

-

Star Wars: Galactic Starcruiser – The Blockbuster to End All Blockbusters

The Star Wars: Galactic Starcruiser was an admirable foray into creating a larp-like experience for mass audiences on a gargantuan scale. It was not perfect, but it was far from a disaster.

-

Together, Apart: Dyadic Play in Larp

in

Designing characters in pairs can lead to two people locked into a singular dynamic that shapes the larp experience around them.